VIEILLIR EN HABITAT PARTICIPATIF : le guide pratique

Destiné aux futurs habitants, professionnels et institutions, ce guide publié par Habitat Participatif France propose des pistes concrètes pour intégrer les enjeux du vieillissement dans les projets d’habitat participatif et inclusif.Read More

Social, affordable and co-operative housing in Europe – Case studies from Switzerland, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark

The Housing Agency of Ireland compiled 44 case studies from Switzerland, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark. The case studies respond to the various challenges of providing adequate housing. The report includes public projects led by government or city authorities, mixed-tenure private developments, and collective schemes led by residents. Like Ireland, all the selected countries have an established tradition of providing housing that is not purely market-oriented to meet a portion of their housing need.Read More

Habicoop – French Federation of Housing Co-operatives

Habicoop, who is it? The original association was created 12 years ago. It became the French Federation of Housing Cooperatives in 2015 and federates about twenty cooperatives. What's a housing cooperative? Its a group of people w ...Read More

Have your say: the Cooperative Identity, from a housing perspective

The Cooperative Identity — the shared values and principles that unite cooperatives worldwide — is being revisited for the first time in decades. The International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) has released Discussion Draft 2 of ...Read More

Research and Analysis Initiative of the International Cooperative Alliance – The Law on Cooperative Housing

The International Legal Research and Analysis Initiative (ILRAI) of the International Cooperative Alliance, coordinated by Cooperative Housing International, provides the first comparative legal analysis of cooperative housing fra ...Read More

Profils d’un mouvement : Les coopératives d’habitation dans le monde

L'habitat coopératif offre des logements abordables à long terme, gérés par les résidents, avec des avantages sociaux, économiques et environnementaux avérés. Malgré son impact mondial, ce secteur reste méconnu.Read More

Public Cooperative Housing Policies: An International Perspective

Explore public policies supporting cooperative housing worldwide in this comprehensive report. Discover how governments and cooperatives collaborate to create sustainable and affordable housing solutions globally.Read More

Financing Co-operative and Mutual Housing

The Commission's final report on Cooperative and Mutual Housing (Bringing Democracy Home) highlighted the need for consideration of the role that cooperative and mutual housing could play in the national housing strategy. The Fina ...Read More

Logement abordable : profils de cinq villes métropolitaines

Par cette publication, nous souhaitons ouvrir le débat sur le logement en tant que droit fondamental et enjeu métropolitain, en mettant en lumière l’expérience de grandes métropoles et dans l’espoir d’inspirer des idées nouvelles pour aborder cet enjeu absolument fondamental de l’urbanisation moderne.Read More

Building Strong Development Cooperation: Partnership Opportunities between Cooperatives and the EU

In 2000, United Nations (UN) member states recognised the need to build global partnerships for development and the exchange of expertise as one of the Millennium Development Goals. Across the international development field, part ...Read More

Raising Capital: The Capital Conundrum for Co-operatives

New report: The Capital Conundrum for Co-operatives "The Capital Conundrum for Co-operatives", a new report released by the Alliance’s Blue Ribbon Commission explores ideas and options available to co-operatives that need suitab ...Read More

Financing Housing Co-operatives in a Credit Crunch

Financing the development of housing co-operatives is a challenge and more so in time of financial restrictions and uncertainty. CHI members discussed the issue during a seminar held in November 2009 in Geneva. Presentations w ...Read More

What’s new in Sustainable Forest Management?

The Forest Products Annual Market Review 2013 reports that the development of new refinement processes has led to the production of new and more affordable wood based products such as cross-laminated timber (CLT). The report sta ...Read More

The Guidance Notes on the Co-operative Principles

Updated Guidance Notes on the Co-operative Principles, edited by David Rodgers, former President of Co-operative Housing InternationalRead More

Promoting Cooperatives – International Labour Organization (ILO) Recommendation 193 on the Promotion of Cooperatives

The ILO views cooperatives as important in improving the living and working conditions of women and men globally as well as making essential infrastructure and services available even in areas neglected by the state and investor-driven enterprises. Cooperatives have a proven record of creating and sustaining employment – they provide over 100 million jobs today; they advance the ILO’s Global Employment Agenda and contribute to promoting decent work.Read More

Profiles of a Movement: Co-operative Housing around the World – Volume One

Cooperative housing offers long-term, affordable homes governed by residents, with proven social, economic, and environmental benefits. Despite its global impact, the sector remains under-recognized.Read More

Students and Housing Cooperatives

Student housing cooperatives have become very popular in the USA and many of these housing co-operatives are members of organizations such as NASCO. Unlike a resident who acquires shares at market rates to earn the right to occupy ...Read More

Good Governance Charter for Housing Co-operatives

The Good Governance Charter for Housing Co-operatives was launched at the ICA Housing Plenary in Manchester in November 2012.It has three parts:A 10-point set of good governance practicesAn interpretive statement for each good p ...Read More

Profiles of a Movement: Co-operative Housing around the World – Volume Two

This second volume of Housing Co-operative Profiles focuses on African countries, showcasing the ingenuity and commitment of cooperators working under difficult conditions. It offers insights into the legal, financial, and historical contexts of housing co-ops, aiming to inspire broader adoption of the model as a solution to the global housing crisis.Read More

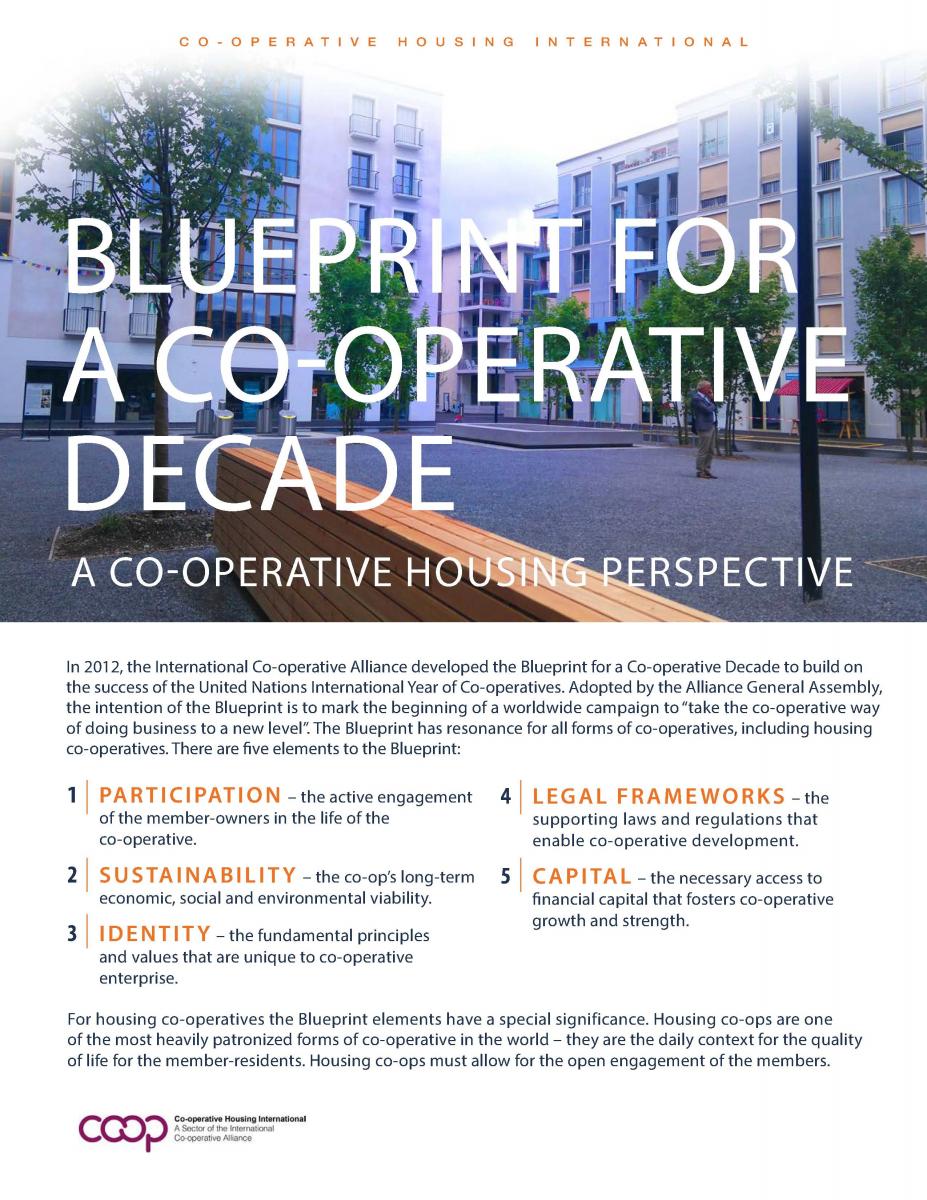

The Blueprint for a Co-operative Decade and its Special Application to the Housing Sector

The Blueprint for a Co-operative Decade is a worldwide campaign to “take the co-operative way of doing business to a new level”. The five key elements of the Blueprint are participation, sustainability, identity, legal frameworks and capital. The Blueprint is particularly relevant to co-operative housing and the Blueprint interpretation for co-operative housing below explains how.Read More